English: sine qua non for Business

Trade, migration, and the increase

and mixture of population must not only have opened people’s eyes, but also

loosened their tongues. It was not

simply that tradesmen inevitably encountered, and sometimes mastered, foreign

languages during their travels, but that this must have forced them also to

ponder the different connotations of key words (if only to avoid either

affronting their hosts or misunderstanding the terms of agreements to

exchange), and thereby come to know new and different views about the most

basic matters. (von Hayek, 1988, p. 106)

“In 2015, out of the total

195 countries in the world, 67 nations have English as the

primary language of 'official status'. Plus there are also 27 countries

where English is spoken as a secondary 'official' language,” honorary professor

of linguistics at the University of Wales and Bangor University, United

Kingdom, David Crystal, mentions and states that over the past hundred years,

English has come to be spoken by more people in more places than ever before. Likewise, according to the World Economic

Forum, in 2017, approximately 1.5 billion people around the world spoke

English, with less than 40 million having it as their mother tongue. Furthermore, a study carried on by the

British Council estimates that by 2020, 2 billion people will be using the

language or learning to use it. But, why

is English so important in the economy of a country and why are people in

business eager to learn the language?

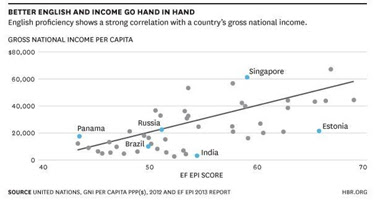

Annually, the Education First English Proficiency

Index (EF

EPI) tests millions of adults over the world in their English skills. In 2017, 1.3 million people in 88 countries

and regions with the median age of 26 took this test. This test is taken voluntarily and in an

online format. The test results have

proven that a country with a higher English proficiency has higher income,

higher quality of life, greater ease of doing business and greater

innovation. Some of these could lead to

a better competitiveness of the country, understanding competitiveness as the

result of assessing 12 pillars conducted by the World Economic Forum, which

include Higher education and training, Institutions, Health and Primary

education and Infrastructure.

In 2013, another result the EF EPI showed

was that “in almost every one of the 60 countries and territories surveyed, a

rise in English proficiency was connected with a rise in per capita income. And

on an individual level, recruiters and HR managers around the world report that

job seekers with exceptional English compared to their country’s level earned

30-50% percent higher salaries.”

So who tops the EF EPI ranking? Sweden, Netherlands, Singapore, Norway,

Denmark, South Africa, Luxembourg, Finland, Slovenia and Germany make the top

10. Eight of the top ten countries are

in Europe. Based on the International

Monetary Fund and United Nation figures, the countries that top the Gross Domestic

Product (GDP) per capita are Monaco, Liechtenstein, Luxembourg, Bermuda,

Iceland, Switzerland, Macau, Norway, Ireland and Qatar; Sweden being in

position number 15. The countries

leading the Human Development Index (HDI) are Norway, Switzerland, Australia, Ireland,

Germany, Iceland, Hong Kong, Sweden, Singapore and Netherlands; Denmark being

in position number 11, United Kingdom in number 14 and Finland 15.

Christopher McCormick, Senior Vice

President for Academic Affairs at

EF Education First accurately states in the article, “The Link Between English and Economics” (2017), published in the World Economic Forum, in collaboration with the Harvard Business Review, that “there is a cutoff mark for that correlation (English and Human Development Index). Low and very low proficiency countries display variable levels of development. However, no country of moderate or higher proficiency falls below “Very High Human Development” on the HDI.” “Given their small size and export-driven economies,” McCormick continues, “the leaders of these nations [Northern European nations] understand that good English is a critical component of their continued economic success.”

EF Education First accurately states in the article, “The Link Between English and Economics” (2017), published in the World Economic Forum, in collaboration with the Harvard Business Review, that “there is a cutoff mark for that correlation (English and Human Development Index). Low and very low proficiency countries display variable levels of development. However, no country of moderate or higher proficiency falls below “Very High Human Development” on the HDI.” “Given their small size and export-driven economies,” McCormick continues, “the leaders of these nations [Northern European nations] understand that good English is a critical component of their continued economic success.”

In 2018, Sweden has reached the first position of the EF

EPI ranking for the fourth time in eight years.

It is evident that English is a

necessity for “the elongated country” due to its high dependence on

exports. Jörgen Weibull, Emeritus

Professor of History, Göteborg University, Sweden and Henrik Enander, former

Lecturer in History, University of Stockholm declare,

“Exports

account for about one-third of Sweden’s GDP. The emphasis has shifted from

export of raw materials and semimanufactured products (pulp, steel, sawn wood)

to finished goods, dominated by engineering products (cars, telecommunications

equipment, hydroelectric

power plant equipment) and, increasingly, high

technology and chemical- and biotechnology.”

On the other hand, Tsedal Neeley,

professor of Business Administration in the Organizational Behavior unit at

Harvard Business School mentions in her article published in 2012, “Global

Business Speaks English”, that “large companies such as Airbus (Netherlands),

Daimler-Chrysler (United States), Fast Retailing (Japan), Nokia (Finland),

Renault (France), Samsung (South Korea), SAP (Germany), Technicolor (France),

and Microsoft in Beijing are including English as their lingua franca, in an attempt to facilitate communication and

performance across geographically diverse functions and business endeavors.” But speaking of Airbus and Nokia and Samsung

we can imagine only big multinationals using English as their lingua franca. A six-month period study was conducted by the

European commission in 2010, having interviewed 40 selected small and

medium-sized international companies across 27 European Union Member

States. The project, Promoting,

Implementing, Mapping Language and Intercultural Communication Strategies

(PIMLICO Project) focused on identifying and describing models of best practice

in these 40 companies which were selected due to their significant trade growth. What was their strategy? Formulating and employing language management

strategies.

In the case of Bolivia, it is ranked

in the 61st position in the EF EPI.

According to the Census of Population and Housing of 2012 in Bolivia, 0,7%

of the population over 6 years old knows how to speak English. How far behind of the top European countries

are we? The British Council held an

English Language Teaching Diagnostic in Bolivia in 2019, with the purpose of

assessing the English level of students and professors in this area according

to the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages, used to evaluate

the achievements of learners of foreign languages (A1 = Breakthrough or

beginner, A2 = Waystage or elementary, B1 = Threshold or intermediate, B2 =

Vantage or upper intermediate, C1 = Effective operational proficiency or

advanced, C2 = Mastery or proficiency). The

study also assessed the interest of learning English in the next two

years.

The diagnostic drew the following

results in terms of the students: 35.6% in A1, 28.9% in A2, 27.4% in B1, 7.4%

in B2 and 0.7% in C2, and the teachers: 1% in A1, 3% in A2, 9% in B1, 27% in

B2, 49% in C1 and 11% in C2. How

competitive, internationally, is it to have the bulk of the students in an A1

or Elementary level? Especially in terms

of business and international trade, an A1 level would hinder the possibilities

of opening Bolivia’s economy efficiently to a globalized world. The good news is that “61.1% [of the people

surveyed] have the intention of studying English in the next two years, while

14.7% say maybe and 24.2% answered no.

It is inevitable to note that today,

English proficiency in a country is not an economic advantage anymore, however

it is the sine quo non of every

globalized country seeking competitiveness in a world that will be more

dependent on international trade, that will need to become an export economy,

not only of goods, but of services as well.

As the 2013 EF EPI report

affirms, “it [English] is increasingly becoming a basic skill needed for the

entire workforce, in the same way that literacy has been transformed in the

last two centuries from an elite privilege into a basic requirement for

informed citizenship.”

REFERENCIAS

Breene, K. (2016, Nov 15). Which countries are best at English as a second language? Retrieved from https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2016/11/which-countries-are-best-at-english-as-a-second-language-4d24c8c8-6cf6-4067-a753-4c82b4bc865b/

British Council. (2013). The English Effect.

Crystal, David (2006). "Chapter 9: English worldwide". In Denison, David; Hogg, Richard M. A History of the English language. Cambridge University Press. pp. 420–439. ISBN 978-0-511-16893-2.

Crystal, D. (2003). English as a global language.

Education First English Proficiency Index (EF EPI). (2017)

Education First English Proficiency Index (EF EPI). (2013)

McCormick, C. (2017, March 16). The Link Between English and Economics. Retrieved from https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2017/03/the-link-between-english-and-economics

Neeley. T, (2012, May). Global Business Speaks English. Retrieved from https://hbr.org/2012/05/global-business-speaks-english

Página Siete. (2019, February 17). Enseñanza de inglés: aumentan estudiantes y faltan profesores

Principales Resultados del Censo Nacional de Población y Vivienda Estado Plurinacional de Bolivia. (2012)

Promoting, Implementing, Mapping Language and Intercultural Communication Strategies (PIMLICO Project). (2011)

von Hayek, F. (1988). The Fatal Conceit: the errors of socialism, p. 106

Autor: Adriana Ayoroa

Nota: Las ideas y opiniones expresadas en este documento son las de los autores y no reflejan necesariamente la posición oficial de la Escuela de la Producción y de la Competitividad (ePC).

Comentarios

Publicar un comentario